A Different Skills Gap with Safety Implications

When the construction industry talks about the skills gap, we tend to think of people not having the right math, welding, rigging, and experience operating heavy equipment. However, there’s another skill, even more fundamental to preserving safety and productivity. That’s the ability for managers and supervisors and their employees to be able to communicate in the same language.

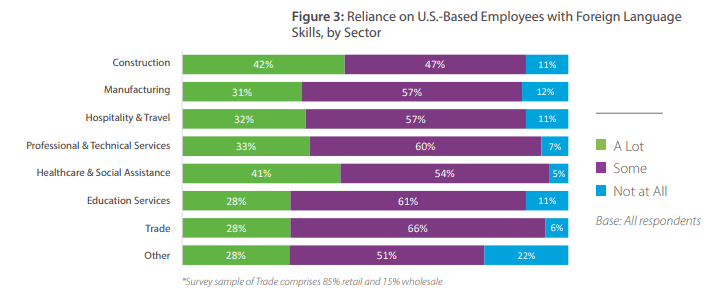

In a 2019 report issued by the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL), construction was identified as having the largest language skills gap—more than any other industry surveyed. Meanwhile, 42 percent of construction employers say they rely “a lot” on employees with foreign language skills, with more than half expecting demand for multilingual workers to grow through 2024.

According to the ACTFL report, about 10 percent of the United States’ overall working-age population are of limited English proficiency. U.S. employers reported that 85% rely on Spanish-speaking employees, but it’s not the only language being heard in the workplace. Other languages represent a significant population also, with Chinese at 34 percent, French at 22 percent, Japanese at 17 percent. Korean and Slavic languages are heard as well.

Language barrier’s impact on safety

While the ACTFL report Making Languages Our Business addresses the loss of business opportunities and language barriers’ effects on the bottom line, for the construction sector, another way the language skills gap impacts business relates to internal operations and project execution. A 2020 article posted on WorkersCompensation.com cited OSHA stating, “language barriers are a factor in 25% of on-the-job accidents.”

OSHA requires that employers provide training in a way that employees can understand, and it allows for crane operators to be tested for certification in a language that the operator understands (1926.1427(h). However, the operator is only permitted to operate equipment that is furnished with materials such as operations manuals and load charts that are written in the language that operator was certified in.

While this makes accommodation for crane operators to become certified, clear communication cannot occur when co-workers are not fluent in the language spoken. Think of the real-time interaction that occurs between riggers, signalers, crane operators, and lift directors. Crane operators often work at the specific direction of others. Clear, precise communication is necessary for crane operators to control and move loads accurately.

Recently, a CIS training class had students that were experienced and highly-skilled crane operators, whose first language was Russian. While they spoke and understood spoken English, their command of written English was preventing them from passing the load charts portion of the written exams.

After two attempts, the CIS trainers and the operators knew they had to do something different for these operators. The employer approved additional time for the trainer to work with the students. Utilizing several translation tools, the trainer provided English language instruction of terms used on load charts and in load chart sample test questions. The trainer went through the lattice boom crane load charts and created multiple scenarios, with different configurations to help the operators understand how to correctly calculate capacity. Students then reverse taught the steps back to the instructor to verify understanding. They worked through making load chart deductions and solved the problems by explaining the steps to the trainer. While this one-on-one training, designed to bridge the language gap, took extra time, it paid off. The operators went from failing scores to celebrating scores in the 90th percentile.

Start with training the employees can understand

An important first step is providing training to riggers and operators in the language they understand. Some of Crane Industry Services’ trainers are multilingual, and we frequently book classes with employers to conduct classes to meet the language needs of their students. We also provide materials that are translated into the languages needed. But to get the most out of this training, trainers need to be prepared.

Recently, one of our trainers showed up to teach a rigging class not knowing that all of the students were Spanish-speaking. Had we known in advance, we would have scheduled a different trainer. Instead, we conducted a quick assessment to determine which of the students had the best command of English as well as rigging skills, and enlisted that student as an interpreter. This individual worked side-by-side with the CIS trainer, who led the hands-on demos. Ultimately, the training was successful. Post-class ratings were excellent.

The quality of the training certainly contributed to the results, but it was also due to another factor. Enlisting a fellow co-worker who spoke the same language as the other students immediately established trust. On the job site, lack of trust—which is an essential component of crane and rigging crew interaction—leads to lack of buy-in to established processes and a reluctancy to report safety concerns.

This is why language barriers must be addressed in more places than the training classroom. It’s critical for leaders in the job site trailer and back at the office to also have command of the language of their workers. Thankfully, about one-third of employers in construction (35 percent) offer their employees language training, according to ACTFL. And it should include native English speakers as well as those whose first language is something else.

Part of this process should be to assess, test, train, and recruit. No matter what skill you are referring to, this model is critical to closing the gap. Assessing, testing and training were among the recommendations made by ACTFL. In addition, they suggest that employers maintain an inventory of linguistic and cultural competencies, which will help classify and cultivate a pipeline of multilingual talent. CIS believes that diversity of language should be reflected in the composition of an organization’s leadership team; and suggests executives identify leaders within their workforce who may have other important skill sets, but lack the required language proficiency.

Manage cultural differences to breakdown barriers

Ultimately, development of a comprehensive strategy for managing language and cultural background can help transform the language vulnerability into a source of competitive advantage. Keeping in mind that people whose first language is not English, also bring different cultural perspectives to the jobsite. In some business cultures, safety is not a priority. Getting the job done, at all cost, even to human lives, may have been the accepted mentality. Without criticism to any culture, communicating that safety is top priority is step one. Next, take a few minutes to learn how tasks where done. Employers can learn safe, innovative practices from workers who may have had fewer resources to complete work. At a minimum, it will alert employers as to what workers may consider to be acceptable in terms of risk.

In moments, any supervisor can Google to gain insights into the cultures and traditions of the people on site. By acknowledging interest and learning a few key phrases, employers build trust and respect. Show the admiration due for what they are accomplishing. This country is in dire need of people willing to work hard, learn and grow. Let’s provide safe and rewarding worksites for them to succeed, and help us meet our goals.

Resources

https://www.workerscompensation.com/news_read.php?id=35239

https://www.osha.gov/publications/bylanguage/spanish

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] article was originally posted here on Centered on Safety June 16, 2021, and was reposted with […]

Comments are closed.